I Was There (1939-1945) by Bro. Edward Earley

In June of 1939 I arrived in Jersey to finish my postulate and then enter the Noviciate. William Drinkwater was my companion. The sun shone brightly during those first few weeks and with the other postulants we went on various walks and excursions. We even visited HMS Jersey; a small battleship paid for by the inhabitants of the island. I remember that on July 14th Bro. Jean-Auguste was awarded the Medaille de Guerre for his services during the First World War. The scholastics joined us for the banquet in his honour. That day we also met Bro. Jean-Joseph, the former Superior-General and Bro. Denis Antoine who was to become the first Canadian Assistant after the following General Chapter.

About a week after the start of the Noviciate war was declared. Several Brothers from Highlands College were mobilised, including Bro. Thadee who had been in charge of the postulants, Bro. Clementin, assistant novice master and Bro. Emilien, the director of the Scholasticate. During the Noviciate we celebrated the Golden Jubilee of the Superior General, Bro. Etienne. I remember one Brother being present in his military uniform, Bro. Gonzague Hallier. One novice, Bro. Bernard Auguste, died during the year. Fortunately, his parents were able to come from Cancale for the funeral. We celebrated the feast of Corpus Christi with a large procession through the streets of St. Helier. Towards the end of the Noviciate I received what was to be my last letter for some time from my eldest brother who was serving with the British army in Norway. Then on July 1st, German soldiers landed in Jersey - the occupation of the Channel Islands had begun. The first German signpost I remember seeing said “Rathaus” (Town Hall). In the autumn of that year, we put together albums for the centenary of the death of our co-founder Fr. Deshayes.

In February of 1941 came the order from the German authorities that the novices and scholastics had to leave for France. The novices were able to find accommodation in the Trappist monastery of Timadeuc. Then in June 1941 Highlands College itself was occupied by German troops. All radio sets were to be handed in to the Germans, although a few crystal sets were secretly kept by certain fearless inhabitants. Fr. Rey s.j. from St. Louis House held the record for making the largest number of crystal sets. I remember that the De La Salle Brothers kept their wireless set in the hollow statue of their Founder in their oratory.

Our chaplain was Rev. Fr. de Tonquedec s.j.. He also preached our annual retreats all through the occupation. During 1942, William Drinkwater and I prepared for our London Matriculation exam which we sat at the Beeches School. We had to wait until after the war to receive the results from London!

Bro. Alberic from Haiti was obliged to leave Jersey when his country entered the war against Germany. He moved to Normandy. 1942 saw us working on the potato harvest with a neighbour who had a tractor, Jack Nicolle. Unfortunately, he was arrested for possessing a radio set that he had kept hidden in his house. He was deported to Germany and died in captivity. The vicar of St. Saviour’s Anglican parish also had a radio which he kept hidden in the organ loft. He too was imprisoned and died in Germany.

Until July of 1942, no-one dared speak of allied victories but after the victory at El Alamein, one never spoke of allied defeats. One day, as I was returning to my quarters from digging up potatoes, some young German soldiers called me over to the window of their dormitory shouting, “We’ve captured Tobruk!” “Who?”, I answered. They informed me that it was a port in N. Africa and showed me their military magazine “Signal”, full of photos of captured British soldiers!

Then they turned the pages to a large map showing the German flag flying all over Europe, from the Atlantic to the Crimea and from Norway to N. Africa. “Not bad, eh? Now we will explain the next move. Here is Tobruk, next to Egypt. The German army will enter that country and proceed through Palestine, then join our troops in the Caucasus mountains and in the autumn (1942) we will capture Moscow. Then in the Spring of next year, our victorious troops will capture London!” “Not possible!” I replied. “But our Fuhrer has planned all of this and his plans will be fulfilled!” “Listen,” I said, “I have to go now (it was time for chapel), but I bet you that I will be in Germany before you reach London!” “Ah, British humour, yes?”, they replied. But two months later I would indeed be on my way to Germany. All non-residents on the Channel Islands were being deported and yet we had committed no crimes.

At the beginning of September 1942, William and I were offered teaching posts at The Beeches. This was wonderful news for us. Prior to this we had simply been studying and doing some work in the garden at Highlands. But the evening after our first teaching day, the Jersey daily paper announced the startling news that all non-residents were to be deported. The next morning, no classes for us. We were handed a letter from the German commander. “You must be at the port at 16.00 hours with your luggage”. Lunch that day was a very sad event. After the meal, I knelt to receive the chaplain’s blessing. We were going into the unknown! At the port 300 people, including children, were assembled. When we went aboard the vessel, we found that we knew nobody else on board.

On arriving at St. Malo the following day, we found that a train was waiting for us at the docks. It took us east through Brittany and Normandy, arriving at the border with Luxemburg at dawn the next morning. That afternoon we reached Biberach in Wurtemburg, Germany. We remained there for six weeks. The menu was two bowls of spinach soup daily. We did once, however, receive a Red Cross food parcel and were fortunate enough to be able to attend Mass once also. After six weeks the single men were transported to Laufen in Bavaria, on the Austrian border near Saltzburg. We were 120 men there detained in what was a castle that during the Middle Ages had been the residence of the Prince-Archbishop of Saltzburg. The camp had housed mainly British POWs in 1940-42; officers taken prisoner at Dunkirk and in N. Africa. Numbers were on the increase with nationals of other allied countries (especially North and South American countries) adding to the British interns.

On November 11th, I was asked to lead the Memorial Service for the dead. Remembrance Day, 1942 was a strange experience. I thought of the dead of World War I (19 14-18) and I remembered the posters I saw as a schoolboy in England: “In Flanders’ fields the poppies grow”. And now we had to think of the present war also, of the dead of the Battle of Britain, pilots and civilians; those who died in the deserts of N. Africa; not forgetting our prisoners in the Far East. Amongst all of these were relatives, school friends, fellow parishioners, neighbours, etc..

In December, we were fortunate enough to obtain a chaplain, a Polish-American Holy Ghost Father from a nearby internee camp. We now had daily Mass for which I was sacristan. Then at Christmas, we celebrated Midnight Mass and were so happy to receive some Red Cross food parcels.

In Laufen, I was present at the reception into the Church of two lads from the camp. We had a special breakfast to celebrate the occasion and presented them with copies of the Sunday Missal that had been sent from the Swiss Catholic Mission. We were also able to buy language books from a firm in Leipzig. I was even asked to give some courses in Spanish. I was only a beginner myself but I was told, “ Teach these students what you have learnt already.” Prisoners of war were encouraged to prepare for certificates issued by London University. My friend William obtained a certificate in German. There was an intern from Haiti who was a former pupil of the Brothers at St. Louis de Gonzague, Port-au-Prince. I even met a young man who had worked with Bro. Donatien Fourrage at St. Mary’s College in Bitterne Park, Southampton. In total, I counted sixteen languages spoken in the camp. Of the French Brothers, there were 360 who had been mobilised in 1939 to help in the war effort. By 1940, 148 were POWs. Other young Brothers in their early twenties were sent to work for a year in Germany to do the STO, “Service du Travail Obligatoire” (Obligatory Work Service).

Whilst speaking to some men who had been imprisoned in Belgium, I happened to mention that my parents were Irish. “Irish? Then you should not be here. In Belgium, several people we knew were freed because of their Irish connections (Ireland was a neutral country). You must apply to return to your college. As a student teacher, you would be of much more use out in a school rather than kept locked up here.” They brought me some paper and a pen. I wrote a courteous letter to the Kommandant. It was January 5th, 1943. But as the days and weeks passed, I soon forgot all about my letter.

During my few weeks in Biberach, I worked in the camp library. But in Laufen, I studied, taught Spanish and worked in the surgery scrubbing the floor once a week. At Easter, I was able to obtain some pots of flowers for the altar in the camp chapel. The corporal who gave them to me was ever so nice. He refused any payment, either in money or in contraband such as real “Nescafe” coffee or chocolate. We heard terrible news of a massacre of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest. Posters were put up on our corridor walls. Who was responsible? The Germans blamed the Russians. Were they right? The Russians denied it. So, representatives from different POW camps were ordered to go and investigate the evidence. Our camp leader, Frank Stroobant, had to go. But on his return, he was ordered not to tell anything. Later, after the war was over, the truth was revealed. It had indeed been the Russians who had carried out this terrible deed; the murder of 4,000 Polish officers.

The German press had been saying, “Britain is starving”, and yet we continued to receive splendid food parcels from the Red Cross. Then later in 1943, we also eventually received some mail from Britain. It had been a long wait for me since the summer of 1940. Every first Sunday of the month, there was a service for the Fallen at eleven o’clock by the village War Memorial whilst Mass was being celebrated in the Franciscan chapel. The Hitler Youth were present and the local Nazi chief would speak, praising the bravery of the young soldiers from Laufen who had died especially on the Russian front and in N. Africa. Those on the Russian front belonged to those who wore the Edelweiss badge. Music was played over the loudspeakers; Handel’s “Largo”. After the war, whenever I heard this piece my thoughts returned to the Cenotaph in that village. Much later, I returned to visit Laufen and was able to inspect the War Memorial. There were three sections for the dead mentioned there; those who had died in France in the 1870 War with Germany, those from World War I who had died on the Western Front and finally column after column of those who had died between 1939-45 mainly in the Ukraine and Russia.

Permission was obtained for internees to go and work on farms outside the camp. The young men found life in the camp so boring with little to do. One man was able to get hold of a radio set, and thus we were able to listen to the BBC News every evening. This made a change from the POW newspaper which only contained German bulletins translated into English.

One day in June, my number 157 was called out at parade. I went to the office and a German captain told me I could return to Jersey. I was so stunned. I asked if he could explain. “You applied to be released, didn’t you?” “Yes,” I replied, “six months ago”. “Have you any money?”, he asked me. “Sir,” I answered, “I left Jersey with £1 and I spent it on a German language book.” “Your country will lend you £10 (106 marks) which you will pay back after the war!” I must confess that I forgot to do so. I did not know at the time but father had written to union leader Ernest Bevin to try and get my release, my father having been a member of the Trade and General Workers Union (T.G.W.U.), though I do not know if this had any influence on my release.

So, I prepared my luggage, underwent a medical examination and finally had to say goodbye to my friends. One man met me and said, while smoking a cigarette, “I hear you are returning to Jersey, Anthony”. “That’s correct.” “I can’t understand you. I wouldn’t go back if you paid.” “Why not?” I asked. “Here I get a food parcel every week now, 50 cigarettes a week, mail from England - I wouldn’t get all that in Jersey, would I?” “No,” I answered, “but, you see, I don’t smoke, we have a large kitchen garden attached to our community in Jersey and I have a teaching job waiting for me.” He walked away smoking his cigarette.

The Germans allowed William, my colleague and another friend to come with me to the village station early that morning. When the train reached its destination, Saltzburg, I put my luggage in the left-luggage room and went for a stroll in the town. I went into a church where Mass was being celebrated. After the service, I went down the side aisle to the altar. It had been a Mass for the dead. A large photo of a young Austrian soldier stood on a stand beside the altar. His aged parents were kneeling there. I asked myself, “Why had this young man died? Were any prayers said for him when he fell? Was he buried by his comrades?”. I returned to the station for a snack with some ration tickets that I had been given.

I was beginning to worry about travelling all the way to Paris on my own on the train when I heard some French voices. I spoke to a group of young Frenchmen. “Are you going to Paris?” “Yes,” they said. I explained who I was. “Can I travel with you?” “Bien sûr!” They turned out to be volunteer workers for the Reich.

On the journey to Paris, we had to stand as the train was full of travellers and refugees. The military were seated in their own coaches. We went to the refreshment car for a soft drink and found some seats. As I turned round to sit in my chair, I noticed a monacled Gestapo gentleman, a stern look in his eye, sipping his cognac. I felt uncomfortable.

The attendant come down the train announcing that dinner was being served. He spoke French. I inquired about a meal. “Have you any ration tickets?” he said. I showed him the tickets that I had, but unfortunately, there was no meat ration ticket. “You can’t have a meal!” he told me, so I had to leave the buffet car. On our arrival at Strasbourg at midnight, myself and my companions were all able to find seats with there being lots of passengers having got off the train. We came into the Gare de l’Est station in Paris at around 10 am. the following morning. I had already mentioned to my companions my problem. “I have one address in Paris, but I don’t know how to get there. I’ve never been to Paris before”. “That’s no problem, mon ami ~ said one of them. “I live in Paris. I’ll show you the way.

But first, we had to eat. We went to a small cafe. “You have ration tickets?” asked the patron. “We’ve only just arrived from Germany.” I placed a packet of English cigarettes on the table. He looked at them curiously. I explained my situation and showed him my Jersey identity card. “Tres bien, come into the back room,” where he served us bangers and mash (saucisses avec de la puree). We then boarded a metro train heading for the Holy Ghost seminary as my companion did not know the exact whereabouts of the address of the Brothers’ community. I explained my problem to the Rector when we got there. “Ah, St. Francois Xavier School? There is a metro station near the church.” So, with the help of my companion, we soon arrived at the community attached to the school, Avenue Duquesne. There I met a former confrere from Cancale who had been with me in Jersey 1939-1940. That evening, after having said “Goodbye!” to my friend, I ate with the community in their dining room and that night I slept between white sheets. I blessed the name of France!

While I was there, I visited Notre Dame Cathedral, Sacre Coeur and went with the pupils to Les Invalides and the Bois de Boulogne. The children sang, “La-haut sur la montagne, il y avait un vieux chalet!” I also visited the College Irlandais (Irish College) and met a Vincentian Father, Fr. Travers, the only priest still in the College. He told me, “I say Mass for the nuns, I have my kitchen garden and my radio set. Not too bad, considering this is an occupied city!”

The Brothers suggested to me that I go to Flers in Normandy. One of the Jersey community was living there. So, one day I took the train from Montparnasse station and began another journey. When I arrived, I found the Brothers living in a private house. The classrooms of their school were now dotted all over the town, as their school property was totally occupied by the Germans. I got a pleasant surprise when Bro. Alberic, the Hatian Brother who had been with me in Jersey, opened the door of the house.

During my stay, I had to sleep in the local seminary. It was by now the summer holidays. There, in Flers, I heard the BBC news in English for the first time during the war. I remember one morning being rather struck on hearing the proverb, “He who sows the wind will reap the whirlwind”, which would turn out to be rather prophetic. From Flers, I moved on to Rennes where I stayed with Bro. Natalis. He suggested that I might like to stay in France to teach. We went together to the Kommandant, but he pointed out that I had to report to the German Police H.Q. in Jersey. He suggested going to the Security Police Office in Rennes. Again, the officer pointed out what was written in the letter my camp Kommandant had given to me. “Why not report to our police in Jersey and then come back to teach in France?” (However, when I eventually reached Jersey, my Superior said to me, “You are not going to leave us again, are you?”)

I then travelled from Rennes to Ploermel with a future postulant. There I met Bro. Etienne, the Superior General, and gave him an account of my time in Germany. Here, the Germans were occupying the ground floor of the Mother House. Some Brothers were teaching in the village in a former monastic community. I visited Josselin, occupied by the Germans, too. There, I met the former Director of Scholastics in Jersey, Bro. Benoit.

Finally, I reached St. Malo, where I was well received by the Brothers at St. Servan. I had to wait there one week, going daily to the German Marine Office to inquire about transport to St. Helier. At St. Malo, I met one day some of the German soldiers who had been stationed at Highlands College in 1942. I explained to them how I came to be there, but to my surprise, they did not explain to me why they were in St. Malo and not London, as they had assured me twelve months earlier. After El Alamein, Stalingrad, the invasion of Sicily, the German star was waning in the sky. I wondered where these soldiers would be twelve months hence. On July 20th, I left St. Malo on a German boat. A German sergeant, a former interpreter in an Allied POW camp who had gone to work in the USA but returned to serve the Fatherland, expressed his surprise when he heard that I had been freed because I was an Irish national. “In my camp, there were several Irish POWs”, he said. I had to explain that they were military, Irishmen who had gone to join the Allied forces and that I was a civilian. About one month after having left Laufen, I arrived back in Jersey. ft was the time of the potato harvest, but our former tractor driver, J. Nicolle, was by now himself in a German prison.

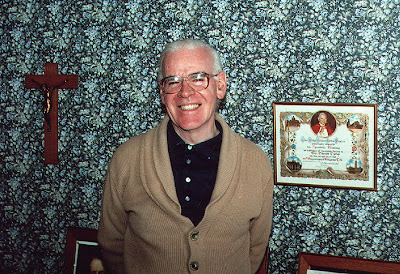

Soon after having arrived, I asked a German sergeant to take my photo which I then sent to England via my friend Willie Drinkwater, who was still in prison in Germany (this was necessary because we could not send letters directly to England). I kept the negatives and then sent them home directly after the war. I returned to my teaching post at The Beeches until the end of the war. The Head asked me if I now knew any German, as he was looking for German teachers.

Since it only meant teaching beginners German, I agreed. It was by now a compulsory subject in Jersey schools. Tim O’Ryan, the Form III form master, told me that he would stay at his desk during the lessons with his form class to help me overcome any discipline problems. There were 57 pupils! Fortunately, we had a good text book, “Deutches Leben” (once the war had finished the lessons stopped).

After our annual retreat, in the summer of 1944, the mental state of one of our community, Bro. Floribert, deteriorated so badly that he had to stay in bed the whole time. Bro. Alpert, watched over him. Bro. Floribert died on Liberation Day, May 8th. Our joy was mixed with grief for our dead confrere. We buried him later that week.

I attended a victory Mass in St. Thomas Parish Church with Bro. Donatien. He was wearing his WW1 medals. I felt as if I was walking alongside a Field Marshal! We drank champagne during the victory celebrations at Highlands. Union Jack flags were flying everywhere on an island that for so long had been living under the flag of foreign invaders. I helped Pierre, our gardener, to hoist the flag at Highlands. On May 24th, the school children of the island attended the march past of our liberators. The military band played and everyone cheered joyously.

We soon received newspapers from Britain, then the first letters from home started to arrive and also from my brothers in the army. They were all well, thank God.

In July, the school year came to an end with the Sports Day and the Speech Day ceremony. Finally, the day arrived when I bade goodbye once more to my island home. I was returning to England. I met some former internee friends on board the overnight ferry. We stood together on the deck at dawn the following morning as the English coast came into view. It was Sunday and the sun was shining. We had all so longed and prayed for this sight. Laus Deo Semper.

The boat came into Southampton. I arrived at the Brothers’ residence, St. Mary’s, in time for breakfast. A few days later I travelled north to Liverpool and home to see my family after being absent so long. I was much older, perhaps a little wiser, and with such a lot to tell.

Comments